Paul Mpagi Sepuya (b.1982), a Los Angeles-based artist working with the medium of photography, creates experimental and collage-like work elaborating on the foundation of portraiture that informs his practice. Using the photographer’s studio as a stage for collaboration, he invites friends and even lovers to be subjects and fellow partakers in the art-making process. Often incorporating and referencing the physical tools of the studio environment into his images—drapery, clamps, stools, light stands, tripods, V-flats, etc.—he pieces together codified compositions exploring the intimate spaces born between photographer and sitter.

In his most recent works, Sepuya uses a mirror as a form of literal and metaphorical introspection. By including or suggesting his own body in the images, they become, in essence, self-portraits—the artist looking at himself and in turn, looking back at us, creating the bridge between artist, audience, and space. As an additional element to his ‘portraiture’, Sepuya adheres large fragments of photographic prints onto the surface of his mirrors, creating a visually disorienting dialogue between what is, in fact, physically real and what is an illusion of form. These prints, which have been torn, severed, and cut into crude graphic shapes, bear the semblance of human flesh—of interlocking body parts. Visual fragments of skin, hair, torsos, arms, legs, and hands are collaged into symbols of physical proximity and intimacy, all the while referencing Sepuya’s deep-rooted knowledge of art history. These highly conceptual works filter through the perspective lens of a Black queer artist, revealing tender notes of Sepuya’s reflections on identity regarding race and sexuality.

© Paul Sepuya, Mirror Study (_MG_1214), 2017

Taking a look at a photograph titled, Mirror Study (_MG_1214), 2017, we can begin to decipher some of the coded language being employed through means of fragmentation and juxtaposition.

Mirror Study (_MG_1214), 2017, a large color photograph measuring 51x34”, depicts a seemingly barren room. A white wall and stone-like floor sets the backdrop; only a hint of the ceiling space is revealed—wooden beams, supports, and an incandescent light. Occupying a majority of the frame, a large mass of jagged triangular shapes congregate at the center, forming a fragmented clump of gesturing hands and a set of legs severed below the knees. It is not easy to decipher at first glance, but judging from the musculature and the prominence of hair (even a slight hint of what resembles a scrotum) the figures depicted look to be of male origin: one Caucasian, one Black. The parts seem to be suspended in midair, encased in separate worlds of darkness and shadow. Just below this kaleidoscopic display, three stick-like protrusions extend out like upside-down antennae, meeting the smooth marble-like surface of the floor.

One of the most inconspicuous elements of the image—strips of black tape—lie in plain sight, subtly camouflaged among the hard edges of this formation. Upon closer inspection, one begins to realize that these bodies do not exist in this world as traditional three-dimensional forms, but rather as an illusion of form. In reality, they exist perceptually on the surface of various photographic prints that have been adhered to an ‘invisible’ mirror. Looking even closer, another important detail reveals itself: a pair of hands, supposedly those of the artist himself, emerges from edge of the frame to greet this corporeal chaos— touching, pointing, and interacting with the surface. These hands exist physically within the world of Sepuya’s photograph, apart from the facade and superficiality of the aforementioned prints.

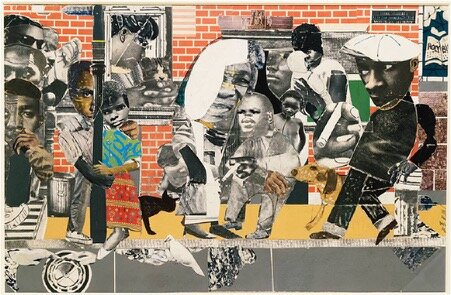

In fragmenting the figure into these distinct visual planes, Sepuya brings attention to the fluidity of the queer body and the multi-faceted dimensions of how it is perceived, constructed, and at times, stigmatized by an exclusive society. Though he primarily works within the discipline of photography, here Sepuya embodies the spirit of a collage artist, calling to mind some of the energetically colorful collage works of the Harlem Renaissance such as those from Romare Bearden. The way in which subject matter presents itself in fragmentary form and shape connotes a complexity of identity and of relationships. In both Sepuya’s and Bearden’s work, the notion of intimacy, community, and togetherness become thematic focal points as each of these artists crowd the frame with a proximity of seemingly animated bodies: engaged, in communion…touching.

© Romare Bearden, Young Students, 1964

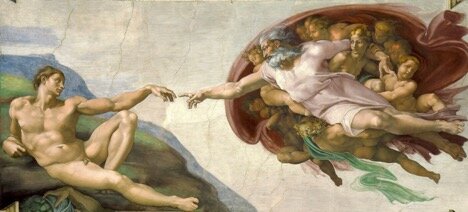

One noteworthy detail from Sepuya’s collage-like assembly is the act of omission; Sepuya has chosen to obscure himself, completely denying his face, legs, and torso of representation. The only hint of his presence comes from the set of hands extending out from the void—hands of the artist, the creator, God in human form. The graceful loving gestures enacted by the artist’s hands—which are mirrored in the images of the printed materials—reference The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo. Contrary to traditional Biblical representations, Adam is presented here as a multi-dimensional queer figure, a product born and reflective of the creator who has lovingly crafted his image.

Michelango, The Creation of Adam, c. 1508–1512

Rembrandt, Self Portrait, 1628-1629

This partial omission of form in self-portraiture goes as far back as Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait, 1628-1629. A young Rembrandt seen here, strategically veiled in velvety shadows, reveals a glint of the interior self, described only by the soft faint outlines of hair and face—suggestions of the body rendered through a nuanced sensitivity to light. At the time, this marked a bold departure from the early conventions of portraiture characterized by even lighting and stiff formulaic postures. In a similar vein, Paul Sepuya pushes the boundaries of what may be considered ‘true’ portraiture in modern contemporary photography. Akin to Rembrandt’s obliteration of figure, Sepuya teases his presence within the image, all the while commanding authorship through the indelible marks of his artistic hand, both literal and figurative. In these two works, spanning hundreds of years apart, both artists seek to redefine what a portrait can be—something that perhaps does not rely solely on the descriptive summations of the surface, but hints at something deeper beyond the frame.